Conservation & Stewardship

Stewardship: Invasive Species

The Darien Land Trust is committed to a stewardship program for the removal of invasive plants and the subsequent replanting with plants native to this part of Connecticut.

The Darien Land Trust is committed to a stewardship program for the removal of invasive plants and the subsequent replanting with plants native to this part of Connecticut.

An invasive plant is a species non-native to an ecosystem, and whose introduction, whether accidental or intentional, causes harm to the environment, economy or human health.

The suppression of biodiversity in our ecology has an enormous social cost. It results from the extinction of many endangered species, each a part of the web of interdependency in local habitats. Fewer birds. Fewer butterflies. Fewer fragrant flowers on the forest floor.

Invasive plants are so successful because they often:

- grow and mature rapidly;

- spread quickly;

- can flower and/or set seed over a long period of time;

- have few known diseases or insects to provide control;

- thrive in many habitats; and

- are difficult to control.

The primary conservation goal is to facilitate natural tree and shrub regeneration and the recovery of native herbaceous plants, tree regeneration, and woody shrubs.

HABITAT RESTORATION PROJECTS

Japanese barberry is just one example of an invasive plant that occurs on Darien Land Trust properties. The DLT has received funding from the US Dept of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service through the EQIP grant program to remove Japanese barberry and other invasive plants on three properties.

Active management to replace the near monoculture of non-native Japanese barberry with a diverse mixture of native species will have multitude benefits by enhancing a variety of ecosystem services.

- Climate change resiliency – Each species is adapted to a range of temperature and precipitation patterns. Increasing the diversity of

species on the sites will ensure that some species will be adapted to whatever climatic changes occur over the next several decades. This principle holds for all layers of a forested plant community: trees, shrubs, herbs, lianas (vines), and thallophytes (mosses and lichens).

species on the sites will ensure that some species will be adapted to whatever climatic changes occur over the next several decades. This principle holds for all layers of a forested plant community: trees, shrubs, herbs, lianas (vines), and thallophytes (mosses and lichens). - Restored nutrient cycling systems – Increased nitrification associated with Japanese barberry infestation are a non-point source of pollution for tributaries of the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound. Japanese barberry infestations have been linked to higher non-native earthworm biomass and increased activity of some earthworm species has been linked to increased phosphorus leaching. Therefore, removal of Japanese barberry could provide a mechanism for reducing nitrogen and phosphorus loading into these tributaries.

- Reduced soil erosion – Leaf litter provides a natural protective barrier to reduce soil erosion. The amount of leaf litter is inversely related to earthworm biomass, e.g., more earthworms – less leaf litter. Because earthworm biomass is higher under Japanese barberry infestations, leaf litter is much lower. One consequence of leaf litter loss can be sheet erosion and bully formation with the eroded soils ending up in adjacent streams. Japanese barberry control can help stabilize soils in coastal forests and thereby reduce sedimentation into tributaries of Long Island Sound.

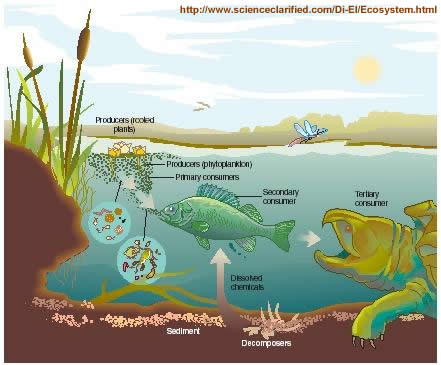

- Improved water quality – Reducing sedimentation and nitrogen and phosphorus loading into the tributaries of the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound will improve the water quality of these streams and adjacent marshes and wetlands. Reduced siltation and turbidity of waterways will benefit finfish and their invertebrate forage base thereby enhancing habitat for resident and migratory fish populations.

- Increased wildlife forage – Currently, the only foraging opportunities available with Japanese barberry are fruit that ripen in October. A diverse community of native plants will provide a variety of foods including soft mast, seeds, and associated native insects the timing of which better coincide with migration and nesting seasons for migratory and resident birds. Japanese barberry has few insect pests, one reason for its importance to the nursery industry, but therefore, provides few feeding opportunities for insectivorous birds including eastern wood pewee, great crested flycatcher, and various warblers and thrushes.

Increased habitat heterogeneity – Each wildlife species has unique nesting and cover requirements. The current monotypic stand of three-foot-tall barberry provides nesting habitat for few species of native birds, and is especially deleterious for ground nesting species such as ovenbirds, Louisiana waterthrush, veeries, and ruffed grouse. The decreased litter layer and dominance of large exotic earthworms associated with barberry stands can also be detrimental for smaller amphibian species including salamanders and some research has suggested a negative correlation between abundance of earthworms and the presence of canopy nesting species such as scarlet tanager.

Increased habitat heterogeneity – Each wildlife species has unique nesting and cover requirements. The current monotypic stand of three-foot-tall barberry provides nesting habitat for few species of native birds, and is especially deleterious for ground nesting species such as ovenbirds, Louisiana waterthrush, veeries, and ruffed grouse. The decreased litter layer and dominance of large exotic earthworms associated with barberry stands can also be detrimental for smaller amphibian species including salamanders and some research has suggested a negative correlation between abundance of earthworms and the presence of canopy nesting species such as scarlet tanager.- Increased pollinator services – The current Japanese barberry monoculture has a 2-3 week-long period of flowering during early spring. This sharply limits the effective foraging period for native pollinators. Increasing plant species diversity would increase the effective foraging period for pollinators and provide a nectar source between early spring terrestrial wildflowers and mid-summer flowering of marsh plants such as pickerelweed and blue flag iris.

- Reduction of Lyme disease risk – Removing Japanese barberry infestations can reduce the number of black legged ticks infected with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi, the causal agent of Lyme disease, by 60%. Reducing the risk of exposure to Lyme disease would not only benefit human and pet health, but should increase the likelihood of passive outdoor recreational activities including hiking and bird watching.

- Increased aesthetics – A wider diversity of species (plants/birds/insects) can increase passive, outdoor recreational activities such as bird watching. For example, these sites would normally have an abundance of spicebush, which is a primary host of the caterpillars of tiger and spicebush swallowtails.

Quick Links

Support Us

Follow Us